Note: This report was published in 2020 and has not been updated since 2021.

Over the last two decades, law enforcement agencies across the United States have been obtaining more and more sophisticated surveillance technologies to collect data. Technologies such as networked cameras, automated license plate readers, and gunshot detection are deployed around the clock, as are the tools to process this data, such as predictive policing software and AI-enhanced video analytics. The last five years have seen a distinct trend in which police have begun deploying all of this technology in conjunction with one another. The technologies, working in concert, are being consolidated and fed into physical locations called Real-Time Crime Centers (RTCCs). These high-tech hubs, filled with walls of TV monitors and computer workstations for sworn officers and civilian analysts, not only exploit huge amounts of data, but also are used to justify an increase in surveillance technology through new "data-driven" or "intelligence-led" policing strategies.

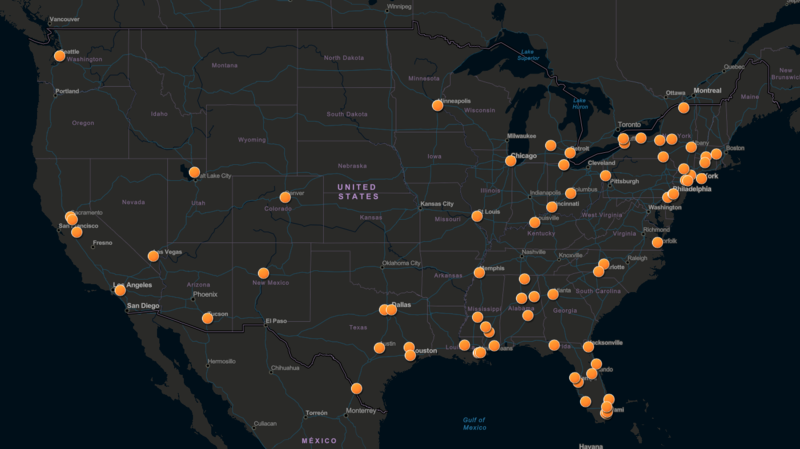

As part of the Atlas of Surveillance project, the Electronic Frontier Foundation and students from the Reynolds School of Journalism at the University of Nevada, Reno have identified more than 80 RTCCs across the United States, with heavy concentrations in the South and the Northeast. In this report, we highlight the capabilities and controversies surrounding 7 of these facilities. As this trend expands, it is crucial that the public understands how the technologies are combined to collect data about people as they move through their day-to-day lives.

RTCCs are similar to Fusion Centers, to the extent the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. We distinguish between the two: fusion centers are technology command centers that function on a larger regional level, are typically controlled by a state-level organization, and are formally part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security's fusion center network. They also focus on distributing information about national security "threats," which are often broadly interpreted. RTCCs are generally focused on municipal or county level activities and focus on a general spectrum of public safety issues, from car thefts to gun crime to situational awareness at public events.

The term “real-time” is also somewhat misleading: while there is often a focus on accessing data in real-time to communicate to first responders, many law enforcement agencies use RTCC to mine historical data to make decisions about the future through "predictive policing," a controversial and largely unproven strategy to identify places where crime could occur or people who might commit crimes.

So far, the Atlas of Surveillance project has identified RTCCs in 29 states, with the highest number in Florida (14) and New York (11); however, Mississippi also stood out with four RTCCs despite being a significantly smaller state. While RTCCs are commonly found in large metropolitan areas, even smaller cities such as Ogden, Utah and Hampton, Virginia have established their own RTCCs. There may be more RTCCs yet to be discovered. In Denver, local officials and news organizations were unaware the Denver Police Department had launched an RTCC and expanded its camera network until Atlas of Surveillance researchers uncovered a job advertisement outlining its capabilities. The Honolulu Police Department has added a RTCC to its 2020-2022 strategic plan.

RTCCs tend to share common defining technological features, the most prominent being access to a surveillance camera network with feeds that are broadcast live onto a wall of TV monitors within a centralized headquarters. The number of cameras can range from just a few hundred, as in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to more than 12,000, as in Atlanta, Georgia, but in all cases the number of cameras have been steadily growing.

RTCCs also go hand-in-hand with gunshot detection technology, especially ShotSpotter, a company that installs sensors throughout neighborhoods in order to listen for and locate suspected gunfire. The majority of RTCCs also tap into automated license plate readers (ALPRs) to track and get real-time alerts on the locations of vehicles. In addition, RTCC staff typically have access to a variety of criminal justice databases and monitor social media feeds.

The starting cost of these RTCCs can range dramatically, from just a few hundred thousand dollars to as much as $11 million, as in New York City. This funding can come from a number of sources, including city budgets, voter-approved bonds, state and federal grants, private institutions, and wealthy individual donors. For example, the Atlanta Loudermilk Operation Shield Video Integration Center started with a $1-million donation from the Loudermilk family, who are real-estate developers, as well as $350,000 from the city. The price tag proved too high for the Fresno Police Department in California, which let go of its part-time RTCC staff in 2019 and ceased all real-time operations at the RTCC in 2020 (although police can still access stored footage from previously installed cameras after crimes occur).

Yet the cost barrier for these systems is steadily dropping. Based at the University of New Orleans, a private organization called Project NOLA provides subsidized cameras and other technologies to cities and provides virtual RTCC software to municipalities through its NOLA National Real-Time Crime Center. So far, Project NOLA has partnered with police departments in Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, Alabama, and Pennsylvania.

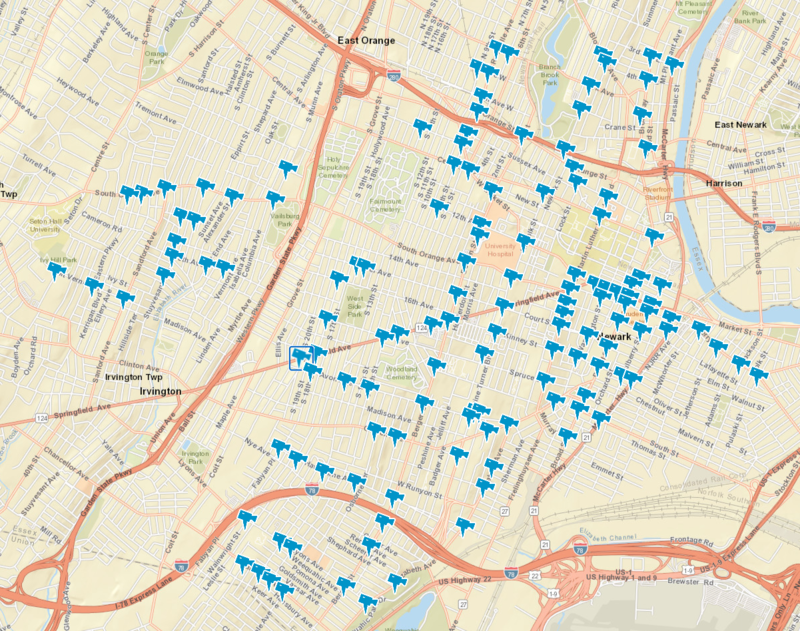

Funding isn't the only way that RTCCs blur the line between public and private surveillance. The Newark, New Jersey RTCC encourages citizens to view live video feeds from cameras across the city through its "Citizen Virtual Patrol" program. Meanwhile, police in Jackson, Mississippi began testing a new system to link doorbell cameras, including Amazon’s Ring, to their RTCC. Similar camera sharing programs are being promoted in Leon County, Florida and New Orleans.

Here are the first seven RTCC case studies:

- Albuquerque Real-Time Crime Center

- Atlanta Loudermilk Video Integration Center

- Detroit Real-Time Crime Center

- Miami Gardens Real-Time Crime Center

- New Orleans Real-Time Crime Center

- Ogden Area Tactical Analysis Center

- Sacramento Real-Time Crime Center

We have also included a profile of the Fresno Real-Time Crime Center, which was temporarily shut down prior to publication.

More profiles are planned in the coming weeks and months. For more information on the technologies used by police, browse the rest of the Atlas of Surveillance site or visit EFF's Street-Level Surveillance hub.

If you know of an RTCC that isn't in our data, email aos@eff.org or fill out our online Google form.

- Dave Maass, Electronic Frontier Foundation, and Hailey Rodis, Reynolds School of Journalism, University of Nevada, Reno.

Credits

This project is based on original research conducted by Prof. Gi Yun’s Cybersecurity, Privacy and Society class at the University of Nevada, Reno, Reynolds School of Journalism: Hunter Drost, Kirk Geller, D. Llaneza, Hailey Rodis, Stone Seuss, Cooper Venzon, Madison Vialpando, Javier Hernandez, and Matthew Hinrichs.

Additional writing and editing: Matthew King, Taylor Johnson, Hailey Rodis, Javier Hernandez, and Madison Vialpando

Published Nov. 13, 2020

Updated Nov. 24, 2020 to include information about the Honolulu Police Department.